By Page H. Gifford, Correspondent

Those who knew Peter Almonte and his work knew that he was more excited by the subjects he painted than the paintings themselves. This was the essence of his work. He had the ability to translate what he saw and felt into images that beckoned the observer to linger and look at the flawless infinite detail in his work. Almonte featured unusual subjects and often used several photos he had taken to create one original work.

A longtime member of the Fluvanna Art Association and the Central Virginia Watercolor Guild, Almonte won numerous awards, and many of his paintings are in private collections. He also exhibited extensively in local galleries. A quiet, thoughtful man, he remained supportive of other artists and mentored them but was always humble in the face of praise for his own work.

Almonte, a former New York City architect, began painting while studying architecture in Cincinnati in the early 1950s. It was his training as an architect that helped him in executing accurate detail within his exquisite watercolors. This is something not easily accomplished by many watercolorists.

Almonte, a former New York City architect, began painting while studying architecture in Cincinnati in the early 1950s. It was his training as an architect that helped him in executing accurate detail within his exquisite watercolors. This is something not easily accomplished by many watercolorists.

A devoted family man, Almonte was married once and even in his 80s would still drive up to New Jersey and visit his son. Then he would return to his studio loft and paint.

Almonte was a resident of Lake Monticello since the 1990s. His house was decorated with various paintings featuring natives working, seaside Asian villages, and churches in Costa Rica. There seemed to be no end to Almonte’s love of other cultures and those influences in his work.

His unique house sat on the lake and his studio was a loft in the bedroom reachable only by a ladder. In that loft he created beautiful paintings with depth and meaning, including his famous Blessing of the Hounds at Grace Episcopal Church, numerous seascapes and European landmarks, marketplaces, the Middle East, and Africa.

Many of his watercolors were scenes taken from trips with the Charlottesville Friendship Force to such places as England, France, Belgium, Germany and Costa Rica. His scenes of Belgian towns are picturesque. His watercolor of a Nigerian warrior captured the man’s ebony skin and the minute details of his headdress with shell beads and braids, along with the firmness and determination in his eye.

He told the story of one picture he painted while on Victoria Island in Lagos, Nigeria, confined to his living quarters during a coup attempt in February 1976 by a group of dissident military men.

“The country’s leader was assassinated, but the coup failed. A sidelight to history is that Nigeria’s current president, President Obasanjo, was then the lieutenant general who took over from the slain leader,” he said in 2007. “On the beach near our quarters, about a dozen of the ringleaders of the failed coup were publicly executed.”

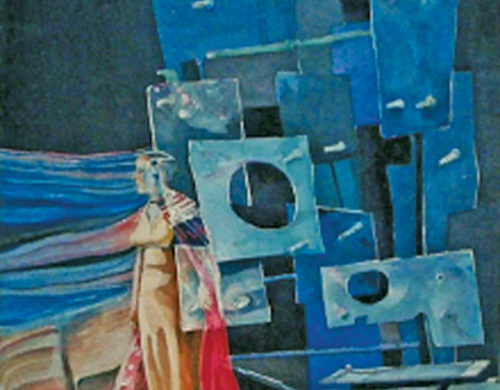

In his later years he experimented with symbolism and more emotional subjects, as exhibited in the theatrical award-winning piece Poetry in Motion. Almonte was also a master of color, blending his colors to convey a certain feeling. In one landscape he portrayed a muted red roof of an old sea shanty on a dock, showing the brightness worn over time from the salt sea air and sun. Another depicts a rowboat drifting on the shores of Ireland, alone and solitary, looking out onto the seas ahead. Some of his paintings even had a pop of deep, bright color.

Unfortunately, Almonte began to notice the trembling in his hands and was eventually diagnosed with Parkinson’s, which over time robbed him of his innate ability to communicate detail in his paintings. Determined, he tried to work around it, but soon gave up painting, much to the disappointment of those who for years had admired his work.

What had always inspired Almonte was what he saw and what he believed would make a good painting. Like other artists, he mixed up images from various travel photos and sometimes came up with a whimsical Shangri La all his own.