By Page H. Gifford

Correspondent

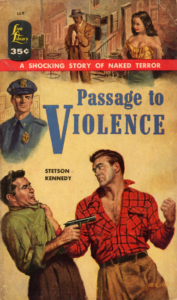

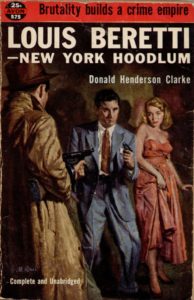

Those familiar with graphic art and illustration may have come across an artist famous for his racy and sensual covers for pulp fiction magazines and paperback bodice rippers during the ’50s and ’60s. The work of former Lake Monticello resident Al Rossi featured coarse-grained men and seductive yet vulnerable women.

Those familiar with graphic art and illustration may have come across an artist famous for his racy and sensual covers for pulp fiction magazines and paperback bodice rippers during the ’50s and ’60s. The work of former Lake Monticello resident Al Rossi featured coarse-grained men and seductive yet vulnerable women.

“It paid the bills,” said his wife, Martha Rossi.

She was close to 30 and a dental hygienist when one of her patients fixed her up with a young artist living in her attic. She and Al Rossi embarked on a journey together, living a modest but comfortable life with their two children.

Al Rossi was the product of a long line of musicians; no one is quite sure how visual art came into his life. His grandfather, Giuseppe Rossi, was a professor of music in Italy and came to America with his musical band. Al Rossi grew up in the Bronx in a large old house, where he would draw and paint. His father taught piano and Al Rossi learned to play.

In a bio he wrote and illustrated as one of his projects for art school, he said that his father’s perseverance and carefully planned lessons were something he struggled with. He continued with lessons to uphold his father’s reputation as a teacher and a musician. By 17 he had become an accomplished pianist.

After the war, he joined a jazz band and traveled prior to entering art school.

After the war, he joined a jazz band and traveled prior to entering art school.

“I didn’t understand jazz but I’d thought I’d give it a try,” said Al Rossi. “To my amazement and later happiness I found myself enjoying the music more and more. I found delight in a new form of musical expression. It is possible to understand both classical music and jazz and to appreciate both.”

Long before he embarked on a career in art, Al Rossi dreamed of becoming an aeronautical engineer. Martha Rossi pointed out the original models he had made, hanging from the ceiling of a spare room. Her husband had described the time that went into his creations, the meticulous calculations and the significant effort.

He did attend Fordham with the expectation of an engineering degree, but when World War II interrupted his plans, he put his life on hold until the war was over. Though war is never a pleasant experience, Al Rossi maintained a positive perspective and said he was glad to have traveled to other places he might never have seen. He also met an Austrian girl named Kitty, who liked to dance and may have had other interests.

“I think she figured she would be a war bride,” said Martha Rossi.

Not too long after Al Rossi returned to the States, he was accepted at the prestigious Pratt Institute in 1950, and later studied at the Arts Student League with Howard Trafton.

After graduating from Pratt, Al Rossi worked for Bantam Press and others as an illustrator of paperback and adventure magazine covers in a genre referred to as pulp fiction. Pulp fiction encompassed hardboiled crime novels, popular during the ’40s and ’50s and known for their graphic violence and strong dialogue.

“Many friends and neighbors posed for Al and he used reference photos as well in his work,” said his wife.

Looking at these covers nowadays evokes a sense of gender-specific roles with tantalizing and naughty glossy comic book colors. The women’s movement changed perceptions and pulp fiction eventually went out of style when its audience no longer demanded it.

Al Rossi also combined his interests in art and engineering by designing and illustrating toys for Ideal, Matchbox, and LJN during his 40-year career. He even sculpted some of the cars he collected over the years, including his beloved MG. The sculpture is masterfully crafted right down to the wire rim spokes in the wheels.

In 1989 Al Rossi retired and he and his wife settled in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania, snug in the woods where he embarked on the third and final journey of his life, painting serene landscapes and figures in oils, watercolors and pastels. He had always harbored the desire to paint, and enjoyed that he was finally free to create without outside input or deadlines.

His landscapes of New England and Nova Scotia, places which he and Martha Rossi often visited, were a stark departure from his earlier work. His work reflected a lone fisherman in a stream of muted, calming watercolor, or the soft strokes and colors of a small harbor scene or a quiet landscape.

Al Rossi contracted leukemia prior to their move to Lake Monticello, but he continued painting towns, farms, rolling pastures, wooded areas, streams and ponds: the things that gave him artistic purpose and peace.

After a long bout with leukemia, Al Rossi died in 2004. He received many art awards, and his work is in business and private collections; Martha Rossi has very few left. But her memories of her husband and his work remain, and her face lights up when she thinks of him.

Al Rossi summed it up best after he began studying at Pratt Institute.

“After three months of fussing with clay rectangles and life classes I found the career I wanted to follow,” he said. “I knew then as I know now that this was the profession I had been seeking. I’d like nothing better than to spend the rest of my life engaged in painting and the like.” And he did.