Names of 110 enslaved people to be etched in stone at Oak Hill Cemetery

Contributed by Tricia Johnson

Scipio. Glasgow. Millie. York. Martha. Major.

The wooded hill sweeps down from the roadside. On a rain-damp and gray morning in early spring, branches, water-dark, artfully frame patches of new, impossibly green leaves and scarlet buds of maple – living cathedral windows to mark this sacred space. Rows of shallow depressions and occasional field stones are all that identify this place as a cemetery. Nearly 200 people lie at rest in unmarked graves in the “old” part of historic Oak Hill Cemetery. The names of those buried there once lost to time. Now, the cemetery is being studied, and the long-forgotten names recovered, in a creative, collaborative effort led by community historians.

The cemetery, tucked away at the end of a quiet road, began as a burial ground for the men, women, and children enslaved at Glenarvon. After Emancipation, it became the final resting place of the people building new lives and a new community as free men and women in West Bottom – people who persevered through the eras of Jim Crow and the civil rights movement, and whose descendants still live here. The men and women and children who call West Bottom home today have roots in this place 300 years deep, reaching back to the practice of slavery.

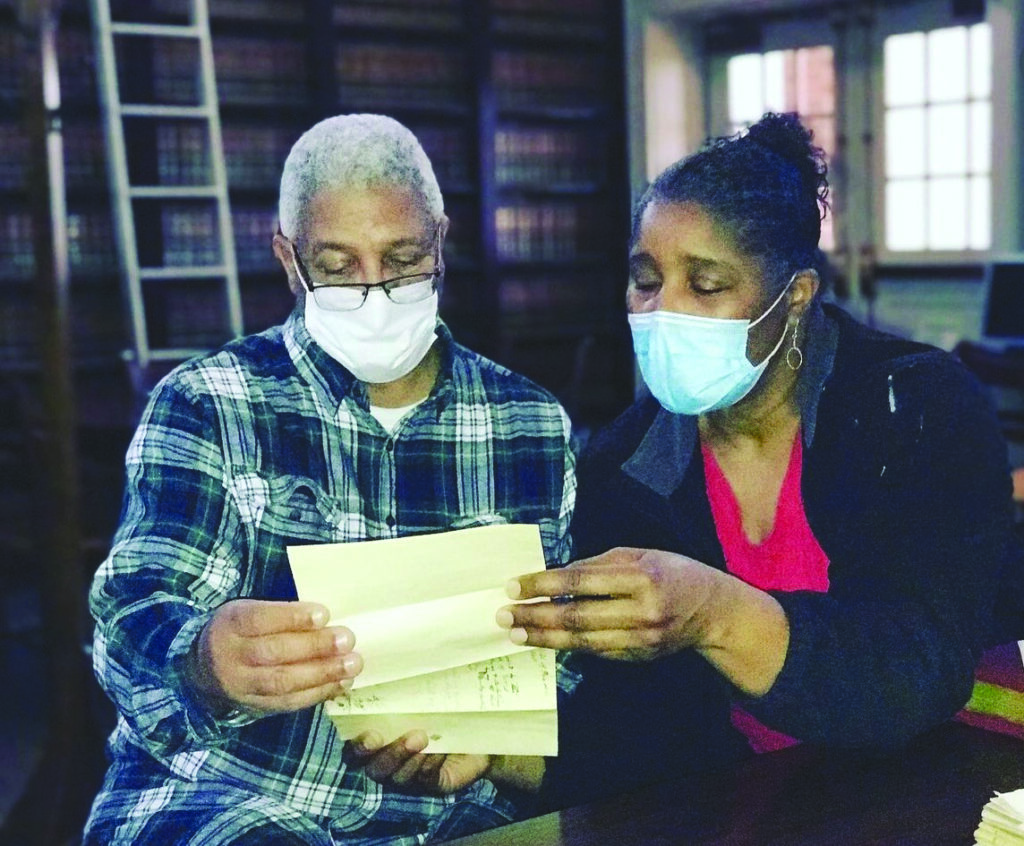

The names tumble off the pages of historic records – death certificates, funeral home accounts, plantation journals, inventories of property, tax records. Finding these names takes hours of research, deciphering nearly illegible handwriting in fragile records, the ink fading and pages tattered, or searching a website one document at a time, peering at the screen in hopes of finding yet another name. Each new name is a new life revealed.

Celey’s child. Carpenter Lewis. Old Send. Pleasant. Louisiana. Ned.

A chain of records beginning with the very earliest documents of this county confirms that those who live in West Bottom today are indeed descended from people who were enslaved on this land even before Fluvanna was formed. Research made it clear that when the land changed ownership, the enslaved men, women, and children were part of the sale, and remained on the land. Some of the names of enslaved people listed in the 1779 inventory of the estate of William King match up with names in the list of enslaved people from tax records of subsequent landowner David Ross in 1782. Some of those match names listed in the 1839 division of the estate of later property owner William Galt the elder, and in the 1851 inventory of enslaved people at the death of William Galt the younger, who had inherited the land from his elder relative. The same names pepper the farm journals of William Galt the younger from 1839-1851. Many names are found in the Fluvanna death register, like Scipio, whose death was reported in 1854 by the man who enslaved him last – William Galt’s brother James. Scipio appeared in a total of five different sets of records including an entry in William Galt’s farm journal that Scipio had found and rescued Galt’s missing, injured young son.

Millie first appeared in the 1779 King inventory; then the 1782 tax record…the 1839 division of the estate…her death was recorded on July 5, 1841, in Galt’s journal where she is called “Old Millie” and is described as having been “a most excellent nurse to young and old.”

Kit. Little Mary. Ananias. Sukey. Eli. Phoebe.

Efforts to study and preserve the cemetery began two years ago with a grant-funded archaeological survey of the wooded hillside; a total of 218 burials were initially identified, 171 without inscribed headstones. Community historians immediately began working to identify the names of as many people buried in those unmarked graves as possible. While they would never be able to tell which burial was which, they were determined to recover as many names of those at rest in Oak Hill as possible.

Searching for these lost names is a remarkable group of community historians. Nadine Armstrong, Melissa Hill, Mahalia Johnson, and William Woodson meet weekly in the fellowship hall at West Bottom Baptist Church and have spent countless hours researching the lives of their ancestors and the history of West Bottom. It isn’t all research at these meetings – there is laughter and fellowship; sometimes there is grief, and tears. Bonds of kinship tighten in the shared effort.

Elias Banks. Moses Bates. Caryann Scruggs. Nancy Barnett. Lizzie Creasy. James Lyles.

Community historian Melissa Hill grew up in West Bottom, and expresses gratitude often to her ancestors, enslaved and free, who she believes experienced enslavement and Jim Crow so that she would not have to. Serving in the leadership of West Bottom Baptist Church, Hill makes things happen. She collaborated with Nadine Armstrong to research and record the names of 110 people buried in unmarked graves at Oak Hill during the first decades of the twentieth century; those names will be etched on one side of the congregate memorial. On the reverse side will be the words of a poem written by Armstrong – “I Have a Name” – and a list of men, women, and children who lived and died enslaved at Glenarvon.

Armstrong echoed Hill’s respect for her ancestors: “I didn’t have to face what they faced; I didn’t have to grow up worrying about what tomorrow brings…will I have food on the table, will I be whipped tomorrow – I don’t have to worry about chains on my feet and my hands and things like that,” Armstrong said. Armstrong has several family members buried at Oak Hill, including her great-great grandparents William and Caroline Palmer, both born into slavery. She feels a deep emotional and spiritual connection to this work and says “It is like setting them free. They are no longer being held in bondage. Slavery bound them,” she explained, “putting their names on that stone…in some way it is releasing their souls.”

Anderson Thompson. Mandy Willis. Ruth Wood. Fannie Bradley. Ben Coleman. Isaiah Woodson.

The collaborators at work in Oak Hill Cemetery extend beyond the geographic confines of West Bottom. Volunteers from across the county and the region have participated in Cemetery Cleanup Days, working to remove decades of brush and scrub growth. Friends at Rivanna Archaeological Services donated hours of their time. Faculty and staff from UVA have come out to give advice. A professional from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources has been out to see the site and offer her thoughts. Staff and volunteers with the Fluvanna Historical Society are regular volunteers.

The initial archaeological work was completed two years ago, but the team from Rivanna Archaeological Services (RAS), drawn by the remarkable level of community engagement, returns often to volunteer with clean up days and to advise the community about preservation matters. Recently, archaeologists Nick Bon-Harper and Susan Palazzo volunteered to ensure the proposed site for the congregate memorial was a good one. By clearing brush and removing a shallow layer of topsoil, searching for changes in the color of the underlying earth, they found signs of a previously unidentified burial. The community immediately began considering other locations for the memorial. When the footing for the memorial is dug, the archaeologists will return to ensure that no burials are disturbed.

Bon-Harper explained his ongoing dedication to the community: “Knowing where your ancestors are buried and caring about those places is an important part of understanding the history of the place and the people who lived there. That in turn builds a stronger sense of community. Our work in support of that is meaningful to us.”

RAS principal Ben Ford explained, “It is a rare occasion that archaeologists have the privilege of working closely with a community that is as passionate about its own history and understanding the past as the West Bottom community. It has been a true pleasure to meet and work with the individuals who have initiated, promoted, and led this fascinating research.”

Quash. Jude. Job. Bristow. Doll. Anniky.

Local grant organizations, including the Charlottesville Area Community Foundation and Virginia Humanities, along with private donors including the Hannah and Wills families, have graciously supported the work. Luck Stone generously donated the memorial stone from their quarry at Shadwell.

The most recent grant funding from Virginia Humanities will pay the cost of the installation and inscription of the congregate memorial, as well as the costs involved with the creation of a film documenting the process by noted Fluvanna documentarian Horace Scruggs.

Scruggs is eager to begin the work. “Documenting this in a permanent way creates a community archive that people can look back on to better understand the significance and importance of these African American cemeteries,” Scruggs said. He also hopes the finished film will serve as an inspiration to other Black communities in Fluvanna and Central Virginia.

Please email the Fluvanna Historical Society at FluvannaHistory@gmail.com or call 434.390.1218 if you are interested in volunteering with this project. The next cemetery cleanup day will be held on Saturday, March 25. Please see the advertisement in this issue for more information about how you can help. Volunteer researchers welcome. Donations are welcome as well. Visit FluvannaHistory.org to donate online – be sure to indicate that your donation is for the Oak Hill Cemetery Project.

The Fluvanna Historical Society would like to thank Virginia Humanities for the generous grant funding that will allow us to install and inscribe this memorial, and to create a documentary of the process.