By Heather Michon

Correspondent

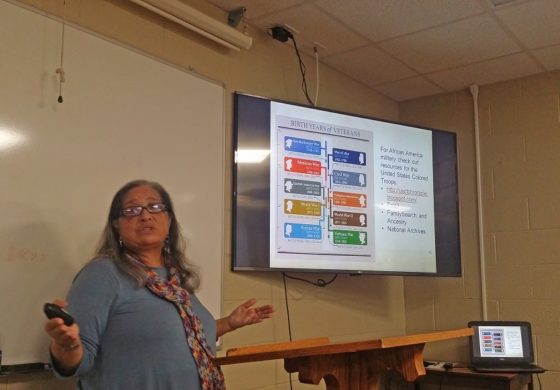

More than 30 people packed into a county conference room Saturday (Feb. 10) for “Hidden Away,” a day-long seminar on African American genealogy put on by the Fluvanna Historical Society.

Fluvanna County has one of Virginia’s more substantial collections of African American genealogical records. The conference gave participants a chance to learn practical skills and then do hands-on research at the county clerk’s office.

In two morning sessions, experts walked the audience through the basics of genealogical research and presented a detailed case study following one descendant’s journey from slavery to freedom.

“This is probably the biggest tip you can get from today: Organize!” said Dr. Shelley Murphy, a genealogist, in the opening session. She said she sees too many family historians with records piled in boxes without a system to find or analyze information.

Murphy, who recently developed and taught a seminar on methods and sources at the Midwestern African American Genealogy Institute (MAAGI) and frequently presents workshops on Genealogy 101, said she always tells students to create timelines to guide research into each descendant.

While the methodology of research is basically the same for African Americans as for European Americans, the nation’s 463-year history of slavery poses unique challenges for genealogists. Records, when kept at all, tended to be incomplete.

“You’re trying to get to the 1870 census,” she said. That was the first federal census after the end of the Civil War and the first ever to include the names of newly-freed slaves. Previous censuses only took a head count of slaves with ages and genders, but no names.

To find family stories dating before 1865, African American genealogists also need to look at information buried in plantation records, inventories, wills, post-war slave narratives, and even snippets of family lore.

For those African Americans whose ancestors lived in the Deep South, where plantation life tended to be much harsher and less well-documented, sometimes only DNA can unravel the mysteries.

But Murphy cautioned that DNA “can open an emotional can of worms,” as it can often bring to light adoptions or illegitimate birth – things that many families might otherwise have kept hidden.

In her case study “Finding Calvin,” genealogist Renate Yarborough Sanders didn’t uncover any family skeletons while researching the history of her paternal great-grandfather Calvin Yarborough, but she did run into many common challenges in trying to answer the seeming simple question: Had Calvin been enslaved?

She knew Calvin was born around 1840, that he had married a woman named Priscilla, and had a family of 11 children before his death around 1910.

When she didn’t find Calvin listed as a free person of color in the 1850 and 1860 census, she knew there was a high probability that he had been a slave.

“Former slaves didn’t always take the surname of their last master, but it’s a good starting point if you have no information to the contrary,” she said. She did note that one aunt had mentioned that their family was supposed to be named Neal.

Sifting through the records of the many slaveholding branches of the Yarborough family and the 1850 and 1860 federal slave inventories, she found he had belonged to James H. Yarborough in 1860 and had passed as property to Yarborough’s second wife when he died.

Digging further, she found that Yarborough had acquired Calvin from his first wife, Elizabeth Neal, upon her death in 1853. At the time of his birth, Calvin had belonged to Elizabeth’s parents and was given to her when her mother died in 1851.

Sanders said she learned a lot from the process of finding Calvin. For one thing, she said, “Family lore usually contains at least a shred of truth.”

She also said that research can take a person to uncomfortable places. “As a descendant of slave ancestors, you have to research slave owners,” she said. Because slaves were valuable property, sometimes the only records of their existence are in these family archives.

“I don’t know any African American is looking for an apology,” said Murphy. “But we want information; we want to know who we are and where we came from.”

The interconnectedness of the past and the present was a theme of the day.

Tricia Johnson, director of the historical society, said the money for the conference, including the digitization of many of Fluvanna County’s core African American records, came from a California woman who visited the county after learning that she was related to a local African American family.

Murphy stressed that genealogy is not something that can be done by internet alone. She said partnering and sharing records with people or going on road trips to archives and cemeteries are often the only ways to blast through the inevitable research roadblocks.

Amazing connections can happen just by talking over a cup of coffee. Johnson told the audience that she and Murphy were chatting at Cuppa Joe’s one day when she mentioned her own roots in Eaton County, Mich.

Before long, they discovered a common connection on their family tree.

“And you know what that means?” Johnson asked. “Cousins!”